Method

Unemployment and Youth Employment in Senegal: A Scoping Review of Achievements, Shortcomings, and Structural Limitations of Public Policies

Mouhammad Dieng

PhD student in political science[1]

Gaston Berger University

Mamadou Diallo

Associate professor, Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Science and Technology

Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar, Senegal

Mame-Penda Ba

Associate professor, political science

Gaston Berger University

Senegal's population is predominantly young, with half of its inhabitants under the age of 19. The current trend, supported by an average annual population growth rate of 2.9%, suggests that this demographic structure will remain stable in the long term. However, this dividend remains hampered by persistent difficulties in integrating young people into the labor market. Having played a decisive role in the country's recent third democratic transition, young people hope that public policies will be put in place to increase employment opportunities. In this article, we conduct a scoping review of policies already implemented in order to identify the dynamics of obstacles and progress in youth employment policies in Senegal between 1999 and 2024.

Database searches yielded 153 studies published in indexed databases, of which 63 ultimately met the inclusion criteria. The data analysis highlighted three major areas of policy success: 1) The creation of direct and indirect jobs; 2) Improved employability; 3) Support for project initiators. At the same time, six major gaps were identified: 1. Insufficient communication and lack of transparency; 2. Weak program monitoring and evaluation, and the precarious nature of the jobs created; 3. Poor coordination of policies; 4. Negative perceptions of the implemented policies; 5. A predominance of ad hoc measures over structural ones; 6. Limited availability of data and resources.

Keywords

Scoping review, job, unemployment, employment policies, youth, socio-professional integration, demography, Senegal, employability, entrepreneurship

Plan of the paper

Introduction

State of Knowledge

Implications for Research

Method

Results

Study Characteristics

The Successes of Youth Employment Policies

Structural Weaknesses in Youth Employment Policies

Discussion

Conclusion

Introduction

Youth unemployment is undeniably one of the most pressing challenges facing contemporary Senegal. This phenomenon is typically understood in terms of its social manifestations and repercussions, rather than through a rigorous evaluation of public programs aimed at combating unemployment, based on reliable statistical data. Although its scale is readily recognized due to its recurrence in public debate, a lack of quantitative assessments persists, fueled by a structural shortage of employment data (Tine & Sall, 2015; Akindes, 2022). This deficiency stems both from a poorly structured labor market and from the difficulty of reaching a consensus on a definition of unemployment, as the conceptual frameworks adopted by international institutions such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) are often considered restrictive and difficult to adapt to predominantly informal economies (ANSD, 2024, p. 4). Indeed, like most Sub-Saharan African countries, Senegal faces the challenge of accurately defining unemployment, particularly due to the lack of contextualized labor market data (Fox & Thomas, 2016). The lack of a consensus definition of unemployment status often complicates the interpretation of economic realities and impedes the implementation of reliable measurement mechanisms.

However, the National Agency for Statistics and Demography (ANSD), a central institution in data production in Senegal, strives to address this deficiency by adopting a definition of unemployment that it considers better suited to local realities[2]. Based on successive surveys conducted by the agency, it appears that the unemployment rate has experienced a concerning trend over the past decade, rising from 10.2% in 2012 (ANSD, 2015) to 23.2% in the first quarter of 2024 (ANSD, 2024). This exponential increase illustrates the seriousness of the phenomenon but also a striking paradox: the contrast between the announced macroeconomic progress and the persistence of underemployment and youth unemployment. Indeed, between 2014 and 2023, the country experienced an average annual economic growth of 5.3% (PSE, 2023, p. 1); however, this was insufficient to generate the jobs needed to reduce unemployment and the quality of the jobs created reveals a labor market dominated by precarious employment.

Faced with this endemic unemployment, the Government of Senegal has made considerable efforts, mobilizing over 544 billion CFA francs (approximately 830 million euros) between 2010 and 2020 (Ministry of Economy, Planning, and Cooperation, 2021). However, the initiatives undertaken—including training programs, placement opportunities, and support for entrepreneurship—have not achieved their intended objectives. Employment policies systematically encounter significant obstacles such as institutional instability, insufficient resources (Sané et al., 2023), poor governance—particularly in financial management (Cabral et al., 2014)—frequent politicization, and a lack of program monitoring and evaluation (World Bank, 2007). They also face inconsistencies—such as overlapping structures, poor targeting, contradictory objectives, and a lack of intersectoral coordination—all of which undermine their impact. Such a situation raises questions regarding the effectiveness, relevance, and overall coherence of public policies.

The objective of this scoping review is therefore to analyze the dynamics of successes and obstacles that have characterized youth employment policies in Senegal over the past twenty years, highlighting the structural and cyclical factors that have influenced their effectiveness. It aims to understand how these policies have evolved in response to socio-economic transformations and the changing needs of youth regarding professional integration.

It also seeks to identify the successes and failures of past policies, highlight the turning points that have shaped the state's approach to youth employment management, pinpoint both the common shortcomings across all policies and those specific to individual ones, provide an overview of evaluations conducted by researchers, and offer recommendations to guide future public action.

State of Knowledge

The question of the effectiveness of youth employment policies is a subject of debate in the scientific literature. Some studies highlight positive effects, showing how support measures succeed in generating momentum conducive to job creation and professional integration (Card et al., 2018). However, a significant portion of the literature reports more nuanced impacts. Several studies point to the limited effectiveness of employment policies, particularly in terms of sustainably reducing unemployment and improving the employability of young people (Kluve et al., 2019). This observation is particularly striking in developing countries, where the effectiveness of these policies is frequently disputed (McKenzie, 2017).

With regard to Senegal, scientific research on the impact of youth employment policies remains limited (Échevin et al., 2013). Most of the available studies mainly highlight the significant gap between the financial and material resources deployed and the results obtained, which are considered insufficient (Barry & Kane, 2022).

Beyond these empirical findings, it is important to situate policies within a pluralistic theoretical framework, shedding light on their epistemologies, programmatic orientations, and structural limitations. Human capital theory, which posits a positive correlation between investment in education/training and individual productivity (Becker, 1975), forms the explicit or implicit foundation of many initiatives focused on youth professionalization. However, this approach is hampered by the reality of a mismatch between the qualifications acquired and the skills actually required in the labor market (Obadić, 2006), which calls into question the ability of training programs to meet the needs of the economy.

Approaches based on labor market segmentation (Doeringer & Piore, 1971) help to understand the logic of dualization between a formal, restricted, and protected segment and an informal sector largely dominated by precarious forms of integration. Some authors emphasize that employment policies tend to overlook these dynamics. Indeed, they tend to view young people as a homogeneous group, without taking into account the social, territorial, and gender inequalities that influence their integration into the labor market. Furthermore, the contrast between active policies (aimed at increasing employability through training, support, or job creation) and passive policies (such as indirect support measures) provides a relevant framework for assessing the consistency of the instruments used (Kraft, 1998).

Placing the analysis within this composite theoretical framework allows us to move beyond a simple descriptive accumulation of programs and, instead, question their foundations, normative orientations, and blind spots. The aim is not so much to pit models against each other as to construct a critical framework for analysis that highlights the frequent disconnect between the conceptual underpinnings, stated ambitions, and concrete implementation strategies in a context marked by institutional fragmentation and volatile public priorities. We will thus show that the measures deployed in Senegal are accumulating without any clear strategic articulation, reflecting more a logic of short-term response to social or political tensions than a structured integration project based on a unified vision of employment development.

Implications for Research

Research on youth employment policies in Senegal is characterized by a focus on the analysis of specific policies or programs. Few studies offer a comprehensive overview of employment policies. This can be partly explained by the complexity of conducting such studies in a context where youth profiles are highly heterogeneous. However, focusing the analysis on a specific category of policies implicitly targets a population of youth whose characteristics align with those policies, risking the exclusion of other groups equally affected by employment issues. This scoping review does not claim exhaustiveness; rather, it aims to compile and synthesize findings from research on specific policies, with the objective of identifying cross-cutting trends essential for a broader understanding of the dynamics and challenges related to youth employment policies in Senegal.

Method

The study adopts the methodological framework of Arksey and O’Malley (2005), a rigorous and well-recognized approach for mapping the state of knowledge in a research field. The flexibility offered by this framework allows for an exhaustive exploration of available studies, while highlighting blind spots and avenues for further research.

It unfolds through five distinct stages. First, the research question is defined in such a way as to cover a broad spectrum of studies conducted on the topic. Next, relevant studies are identified through a documentary strategy using multiple databases and explicit inclusion criteria. The next step is a filtering process that retains only studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Fourth, data are extracted and organized to highlight key information and map the available knowledge and gaps. Finally, analyzing and contextualizing the data highlights the dominant themes and gaps in the literature.

This study centers on the following central question: What are the responses of the State in addressing youth unemployment in Senegal? From this main question, two additional questions guided the analysis: How have these dynamics evolved over the past twenty years? What are the key achievements and challenges of youth employment policies in Senegal?

The review drew on studies published from 1999 to 2024. This timeframe is justified by its historical importance, corresponding to a pivotal political period initiated by the first democratic transition, during which the state intensified its involvement in youth employment in response to the decisive role young people played in the transition and the considerable expectations they embodied.

Studies were selected through searches in online databases, including Google Scholar, HAL-SHS, ResearchGate, BNUCAD, and Scholar Vox. To identify relevant publications, we combined keywords (employment policies, employment, unemployment, youth, Senegal, employability) using standard Boolean operators (AND, OR), progressively refining the results. Additionally, truncation was used to broaden the search by capturing lexical variations of the chosen terms. Additional related keywords were used to broaden the scope of the search, including: socio-professional integration, labor market, access to employment, training–employment alignment, and self-employment.

Table 1: Keywords and keywords combinations

Main keywords | Employment, employment policies, unemployment, youth, Senegal, employability |

Boolean operators | (Employment policies OR Employment OR Unemployment) AND (Young people AND Senegal), (Employment policies AND Employability) AND (Young people AND Senegal), (Socio-professional integration OR Job market) AND (Access to employment OR Training-job match) |

Related keywords | Social and professional integration, job market, access to employment, entrepreneurship, self-employment, training-employment match, career path. |

Truncation | Employment*, Unemployment*, Youth*, Employability* (Policy* AND Employment*) AND (Unemployment* AND Youth*), Policy* |

Publications issued by national institutions as well as those produced by international organizations (IOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), were also thoroughly reviewed in order to capture non-academic perspectives. Such a diversity of sources enhances the analysis, offering a more holistic view of employment policies. It provides insight into macroeconomic and institutional factors along with social dynamics and local constraints affecting policy effectiveness.

For this review, we included all studies examining employment policies from 1999 to 2024, a period characterized by strongly proactive public interventions. This period represents a paradigmatic phase in public employment policy, marked by a governmental shift toward reinforcing initiatives to tackle unemployment. We included not only studies focusing on specific policies, but also those comparing policies implemented at different times under successive political regimes. This enables us to trace the development of state strategies and their impact over time.

Conversely, we excluded studies that dealt with unemployment or employment in broad terms, without a specific focus on state-led public policy analysis. This distinction is crucial, as it directs focus toward the scope and effectiveness of state actions rather than broad labor market observations. Accordingly, studies focusing solely on individual career trajectories, without connection to state initiatives, were excluded. The same applies to studies that had no direct link to specific interventions by the Senegalese government in this area.

Finally, we considered both studies focused solely on Senegal and those covering broader regions that included relevant insights into the Senegalese context. We nonetheless excluded studies outside the relevant geographical scope, even when they satisfied other inclusion criteria.

A key limitation of this scoping review should be noted. Only studies available online were included, which may create a selection bias by potentially excluding relevant work published in local journals or in printed works not accessible on the internet.

The article selection process followed an approach that ensures the consistency of the selected corpus. First, we reviewed the studies based on the established inclusion criteria. This step involved, among other things, a deduplication phase to eliminate redundant occurrences and optimize the reliability of the initial selection. Second, we undertook a critical review of the preselected studies. This review had three main objectives: to ensure that there were no remaining duplicates, to assess the relevance of the exclusion criteria applied, and to examine the compliance of the selected studies with the inclusion criteria defined upstream.

Figure 1: Prisma diagram showing the selection process for included studies

Results

Following the bibliographic search in the selected electronic databases, a total of 358 studies were initially identified. A deduplication phase reduced this number to 153 articles, eliminating not only apparent duplicates but also documents with identical content despite different titles, those with provisional and final versions, documents published by several institutions under various titles and often with distinct introductions, as well as studies already included and reproduced in another format. At the end of this stage, 153 unique studies were selected.

An initial screening based on an examination of the titles led to the exclusion of 44 studies, while an evaluation of the abstracts resulted in the elimination of 34 other studies, which were deemed irrelevant to the objective of the review.

After this sorting phase, 75 studies were selected for full reading. However, 10 of these were discarded because their analysis focused on the integration of different profiles of young people (students, rural youth, etc.) without establishing a direct link with employment policies. In addition, two other studies were excluded: one due to its geographical area, and the other due to its publication period not meeting the scope review criteria.

Thus, after this selection process, 63 studies were retained, providing a representative documentary basis for the analysis (Figure 1).

Study Characteristics

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the 63 studies selected, organized according to various criteria. The studies were first classified by type, then categorized according to their geographical context of publication. While the majority of studies (53) focus exclusively on Senegal, some take a broader perspective, encompassing regional or international contexts that include Senegal. Finally, the studies were divided according to their publication period, which was divided into three distinct phases: 1999-2010, corresponding mainly to research on policies initiated in the aftermath of the first political change in Senegal; 2011-2020, linked to developments under the second change of government; and finally, 2021-2024, a period marked by intensifying concerns about youth employment in a social context of fierce protest.

Table 3 summarizes the main weaknesses of employment policies as well as their notable advances highlighted by the various studies selected. Each item listed is supported by specific references in order to establish these findings on a verifiable empirical basis.

Table 4 provides an analytical overview of the main employment policies identified in the studies examined. It identifies their achievements and highlights their shortcomings, whether structural, financial, or conceptual. He then highlights the benefits these policies offer young people in terms of professional integration and improved access to the labor market. At the same time, he emphasizes the specific constraints they continue to face.

Table 2: Characteristics of the studies selected

Categories | Details | Total |

Types of studies | Theoretical and analytical study | 15 |

| Policy Brief | 4 |

| Mixed empirical study | 1 |

| Descriptive and situational study | 9 |

| Impact assessment (quantitative methodology) | 6 |

| Policy study | 14 |

| Empirical (quantitative) study | 5 |

| Qualitative survey | 2 |

| Government/institutional document | 6 |

Mixed and comparative study | 1 | |

Geographical context | Africa | 2 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1 |

| Developing countries | 2 |

| Senegal | 54 |

| West Africa | 3 |

| French-speaking Africa | 1 |

Publication period | 1999 - 2010 | 7 |

2011 - 2020 | 30 | |

| 2021 - 2024 | 26 |

Table 3: Main themes drawn from the selected studies

Main theme | Subtopics | Quotes from relevant studies |

Gaps | Insufficient communication and lack of transparency | ● Lack of transparency and poor accessibility of management accounts, insufficient accounting reports, lack of awareness of programs among young people, evidence of misappropriation of objectives, significant shortcomings in communication, information, and awareness-raising. (Diallo et al., 2023, p. 10), (Timbuktu Institute, 2020, p. 1), (Sané et al., 2023b, p. 10), (Kane et al., 2018, p. 11-12), (Diallo et al., 2023, p. 18), (CFYE, 2021, p. 8) et (Sané et al., 2022, p. 31) |

Deficiencies in monitoring and evaluation and precariousness of jobs created | ● Poor integration of monitoring and evaluation practices, few ex-post evaluations, lack of control and monitoring and evaluation of programs in the field, few economic indicators on the impact of programs, lack of evaluation of the sustainability and quality of jobs created, precarious nature of the majority of jobs created. (Diallo et al., 2023, p. 17), (Baumann, 2016a, p. 223), (Cabral et al., 2014b, p. 53), (Baumann, 2016b, p. 231), (Banque Mondiale, 2007b, p. 85), (Kane et al., 2021, p. 2), (OIE, 2024, p. 34), (Diagne, 2024, p. 5-6) et Banque Mondiale, 2023) | |

| Multiple policies and lack of coordination | ● Lack of coordination between structures, proliferation of stakeholders, overlapping objectives, lack of complementarity, poor visibility of public action, insufficient consideration of previous efforts (Ndoye, 2020, p. 56), (Tsambou et al., 2022, p. 4), (Banque Mondiale, 2007b, p. 88), (Tine & Sall, 2015b, p. 7), (Diallo & al., 2022, p. 60), (Bourkane Ly et al., 2019, p. 12), (Sané et al., 2022, p. 19), (Diallo et al., 2023, p. 18), (Ba et al., 2012, p. 17) et (Sarr, 2004, p. 11) |

Negative perceptions | ● Perceptions of policy ineffectiveness, suspicions of political influence, criticism of policies perceived as detached from the realities on the ground (Sambou, 2020, p. 6), (Sané et al., 2023b, p. 13), (Diallo et al., 2023, p. 19), (Kane et al., 2018, p. 24), (Labrune-Badiane, 2016, p. 53), (M. A. Diallo & H. Diallo, 2021, p. 7), (Timbuktu Institute, 2020, p. 1) et (M. A. Diallo, 2023, p. 4) | |

| Predominance of ad hoc andnon-structural measures | ● Policies primarily linked to political mandates, persistence of subsistence entrepreneurship.(Tine & Sall, 2015b, p. 6), (Sylla, 2023, p. 21) et (Kane et al., 2020, p. 614) |

Low availability of data and resources | ● Lack of reliable statistical data, relatively decontextualized systems, lack of resources and partners, scarcity of empirical evidence on the evaluation of public employment services, fragility of existing data, low share of resources in GDP (Akindes, 2022b, p. 11), (Tine & Sall, 2015b, p. 8), (Sané et al., 2023b, p. 10), (Fox & Thomas, 2016), (Baumann, 2016a, p. 220), (Kamga, 2019, p. 23), (Barlet et al., 2011, p. 33), (Banque Mondiale, 2007b, p. 87-88), (Sylla, 2023, p. 19), (Diallo & al., 2022, p. 60), (Seck, 2004, p. 60), (Massing et al., 2014, p. 14) et (Ndao, 2010, p. 7) | |

Successes | Creation of direct/indirect jobs | ● Job creation through support for entrepreneurship, investments in businesses, investments in priority sectors, and the development of agricultural projects. (Ozor & Nyambane, 2024, p. 12), (Ndoye, 2020, p. 200), (Ministère de la Jeunesse, de l’Emploi et de la Promotion des Valeurs civiques, 2014, p. 52), (Bourkane Ly et al., 2019, p. 15), (Baumann, 2016a, p. 221), (Conseil Economique Social et Environnemental, 2013, p. 144), (Conseil Economique Social et Environnemental (CESE), 2021, p. 33), (Ministère de l’Économie du Plan et de la Coopération, 2021, p. 6) et (Ministère de l’économie, des finances et de plan, 2018, p. 102) |

Improved employability | ● Easier access to quality jobs, positive influence on obtaining permanent or fixed-term contracts. (Tsambou et al., 2022, p. 37), (Kane et al., 2022, p. 74), (Ndoye, 2020, p. 179), (Tsambou et al., 2024, p. 16), (Kane et al., 2018, p. 29), (Ministère de l’Économie du Plan et de la Coopération, 2021, p. 6), (Busson, 2021, p. 18) |

Table 4: Summary of the main policies studied

Policies | Government | Young people | ||

Achievements | Limits | Benefits | Limits | |

State-Employers Agreement (CEE) | Regardless of the program offered by the national State-employer agreement, 30 % of beneficiaries work on permanent contracts, over 42 % on fixed-term contracts, 19 % on verbal contracts, and only 8 % work without a contract. | Existence of beneficiary selection bias. | Improved employability, positive and significant impact on obtaining employment. | Existence of imbalances in profits between men and women and insufficient scale of deployment. |

National Agency for the Promotion of Youth Employment (ANPEJ) | Between 2014 and 2021, ANPEJ helped more than 16,000 young people find sustainable employment. | Poor territorial coverage, overlapping missions and lack of coordination with other structures, and insufficient financial and technical resources. | Personalized support, facilitation of access to financing, networking, and opportunities. | Limited access to information, limited capacity, regional disparities, and lack of post-training follow-up. |

General Delegation for Rapid Entrepreneurship among Women and Young People (DER/FJ) | - 115 billion CFA francs invested in supporting entrepreneurial initiatives- 252,657 entrepreneurial initiatives financed, including 6,286 microbusinesses and SMEs receiving support- 15,437 beneficiaries trained in entrepreneurial skills- 1,862 companies receiving technical assistance- 500 startups supported, including 300 funded | Slow processing of applications, overlapping responsibilities with other structures, insufficient resources, and limited scope of nano-loans. | Credit facilities, managerial and technical training opportunities, and networking. | Long waiting times, low feasibility of rapid entrepreneurship, persistent procedural burdens. |

Priority Investment GuaranteeFund (FONGIP) | Between 2013 and 2020, 63,757 jobs were created and/or consolidated, mainly in agriculture and agribusiness. | Dependence on public funds, problems with monitoring funded projects, challenges related to repayments, and risks of sectoral concentration. | Support for startups and innovative projects, facilitation of access to credit, capacity building, support for women entrepreneurs. | Lack of direct financing, limited funding amounts, and strict eligibility criteria. |

Vocational and Technical Training Financing Fund (3FPT) | 90 billion mobilized, nearly 400,000 people trained, and 676 projects funded in ten years. | Dependence on public resources. | - The 3FPT funds up to 90 % or 100 % of training costs for young people aged 16 to 40, with or without educational qualifications, thereby facilitating their integration into the workforce.- Diversity of training programs- Support for self-employment | Limited access to information. |

National Agency for Agricultural Integration and Development (ANIDA) | Since 2006, development of village farms ranging from 15 to 100 hectares, increasing from 100 farms in 2015 to 443 farms in 2021 and creating more than 35,000 jobs. | Delays in implementation and difficulties in extending to a larger number of beneficiaries. | Employment opportunities through modern farms, acquisition of technical and entrepreneurial skills, access to infrastructure, modern equipment, and financing. | Difficulties in accessing land, logistical challenges for young people in rural areas, challenges related to a limited market, challenges intrinsic to the agricultural sector. |

Senegalese Program for Youth Entrepreneurship (PSEJ) | Since its inception until 2018, the program has trained nearly 2,000 higher education graduates in entrepreneurship and in priority areas of the PSE such as agriculture, ICT, transportation, and logistics, in addition to providing technical and financial support to more than 20 innovative companies. | Lack of relevance in targeting profiles, insufficient resources, and poor publicity for the program. | Certificate program in entrepreneurship leading to the Higher Diploma in Entrepreneurial Management (DISEM), financing facilities, encouragement of innovation, training, and support | Limited access to information. |

National Youth Promotion Fund (FNPJ) | Between 2000 and 2012, nearly 2,600 projects were funded and more than 12,626 direct jobs were created. | Very small scale and failures in the reimbursement tracking system. | Credit facilities | Political interference in the granting of loans, according to the Court of Auditors' report on the audit of the FNPJ accounts (2004), pages 58 to 64. |

The Successes of Youth Employment Policies

Despite their inability to substantially reduce the massive unemployment affecting Senegalese youth, employment policies have nevertheless generated some positive results, although their effects remain limited and fragmented. We have identified three main successes which, while not solving the problem in depth, represent significant progress: direct/indirect job creation, improved employability, and support for project leaders.

- Direct/indirect job creation

Certain employment policies have demonstrated their ability to generate both direct and indirect jobs, constituting partial but significant successes. There is therefore a concrete, albeit limited, impact from certain initiatives. For example, Ozor and Nyambane (2024) detailed the jobs generated by the ANPEJ[3], while the Ministry of Youth, Employment, and the Promotion of Civic Values (2014) quantified the jobs created under the National State-Employer Agreement (CNEE). Bourkane Ly et al. (2019) highlight the employment opportunities that have resulted from investments in the priority sectors of the Emerging Senegal Plan (PSE). Furthermore, the Ministry of Economy, Planning, and Cooperation (2021) highlighted the results of various initiatives such as the DER/FJ, FONGIP, FONSIS, ANIDA, and ANPEJ, which, despite their disparities, all contribute to job creation in various sectors. However, even when the results of all these initiatives are combined, the number of jobs generated remains largely insufficient to absorb youth unemployment on a national scale.

- Improving employability

Some researchers have suggested that the employment challenge in Senegal is more a question of employability than job availability. In their view, the majority of young people, even when opportunities are available, do not meet the required level of employability. This observation has inspired the formulation of policies aimed at strengthening the employability of young people, including the CNEE, as highlighted by Tsambou et al. (2022). Similarly, the School-Business Training Program (PF2E), studied by Busson (2021) has demonstrated its importance in filling gaps in practical skills and building bridges between theoretical training and the requirements of businesses.

- Support for project leaders

Given that it is impossible for the public and private sectors to absorb all of the unemployed, one of the government's most recent strategies aims to promote entrepreneurship and self-employment among young people. With this in mind, several support structures dedicated to project leaders have been set up, including the DER/FJ, which is widely recognized for its work (see DER/FJ, 2024; AUC and GIZ, 2020).

Structural Weaknesses in Youth Employment Policies

Analysis of the selected studies revealed six major shortcomings in youth employment policies in Senegal : insufficient communication and lack of transparency, inadequate program monitoring and evaluation, precariousness of the jobs created, poor policy coordination, negative perceptions, predominance of ad hoc rather than structural measures, and limited availability of data and resources.

- Limited availability of data and resources

Data management is essential for effective employment policies, as it provides a clear understanding of market needs and allows for monitoring of results. The reliability of data therefore determines the relevance and contextualization of interventions. However, as Akindes (2022) laments, employment policies in Senegal are hampered by weak statistical data. Fox and Thomas (2016), note that the lack of reliable data compromises the contextualization of policies to the real needs of young people. In addition, the structures responsible for collecting and processing this information often struggle to perform their functions optimally, as Barlet et al. (2011) show it. At the same time, the lack of financial resources adds to the challenges faced by these structures. According to the World Bank (2007), budgetary constraints are one of the major obstacles to the impact of employment policies.

- Insufficient communication and lack of transparency

Several studies have highlighted the fact that youth employment policies often suffer from a lack of awareness among their target audience. Kane et al. (2018), in their survey report, note that young people are often unaware of the measures in place, largely ignorant of the programs designed to facilitate their entry into the labor market. The Timbuktu Institute (2020) emphasizes that, despite significant efforts by the government in terms of communication, these efforts have proven ineffective, illustrating a shortcoming in information dissemination strategies. The difficulty in accessing information is also closely linked to a lack of transparency, particularly with regard to the availability and clarity of financial reports from the structures involved, as highlighted by Diallo et al. (2023) in their review. The limited transparency surrounding the objectives and results of the programs, combined with suspicions of misappropriation of objectives noted by Sané et al. (2023) reinforces a sense of mistrust toward these mechanisms.

- Deficiencies in monitoring and evaluation and precariousness of jobs created

The literature highlights a structural deficit in monitoring and evaluation in employment policies, a weakness that has been repeatedly mentioned (see Cabral et al., 2014; Kane et al., 2021; OIE, 2024; Diagne, 2024). Although the integration of monitoring and evaluation practices is frequently mentioned by the responsible bodies, these are often limited to mere declarations of intent, without any concrete application (Diallo et al., (2023). This shortcoming complicates any attempt to obtain a reliable overview of the dynamics of employment policies (Baumann, 2016a). Moreover, the lack of rigorous evaluation makes it impossible to properly assess the real impact of these measures on the quality of the jobs created. In fact, according to the World Bank (2023), a significant proportion of jobs remain precarious, which raises the issue of job stability and sustainability for young people.

- Multiple policies and lack of coordination

A recurring issue identified in the literature is the dispersion of efforts made by the State. The 2007 World Bank report, cited by Ndoye (2020) highlights this dispersion as one of the fundamental causes of the ineffectiveness observed in current and past systems. The real problem lies not so much in the multiplicity of policies as in the lack of coordination between them. Sané et al. (2022) in their article, refer to a “balkanized’’ public employment service to illustrate the lack of synergy between the various initiatives. Although rationalization initiatives have been observed, such as the creation of the ANPEJ, Tsambou et al. (2022) argue that this measure has not been able to reverse the trend.

- Negative perceptions of implemented policies

For a public policy to fully achieve its objectives, it is essential that beneficiaries embrace it, as this determines both its effectiveness and legitimacy. Several studies, notably those by Sambou (2020), Sané et al. (2023), and Kane et al. (2018), highlight negative perceptions that hinder young people's acceptance of policies created for their benefit. This situation can be explained by various factors, including suspicions of political patronage, cited by Labrune-Badiane (2016) and Diallo et al. (2023), which appear to be among the most recurrent ones. They fuel a climate of mistrust towards public employment schemes and make it difficult to mobilize young people around the proposed measures.

- Predominance of ad hoc and non-structural measures

A review of the literature also reveals a lack of continuity in policies, attributable to a succession of short-lived measures that respond more to immediate objectives than to fundamental issues. Each political regime tends to introduce initiatives geared toward short-term visible results, without sufficiently integrating a structural vision of the problem. As Tine and Sall (2015) point out, these short-term interventions offer temporary solutions but fail to address the underlying problems. Sylla (2023), while praising the territorial approach of the “Employment Hubs,” deplores the ad hoc nature of the initiative which lacks a sustainable framework to guarantee ongoing benefits.

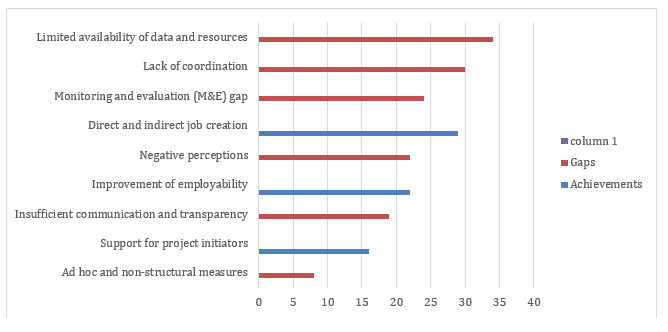

Figure 2: Number of articles per sub-theme (n out of the 63 articles selected)

The graph above illustrates the thematic distribution of citations identified in the analyzed corpus. The numbers shown correspond to the number of articles, among the 63 selected, in which each sub-theme was mentioned. This representation is the result of combined manual and automatic coding using NVIVO software.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to examine the contrasting dynamics that have shaped public policies on youth employment in Senegal over the past 20 years. The three major successes identified, demonstrate the potential of the policies implemented to generate both direct and indirect jobs. However, their scope is tempered by limitations, including the insufficient number of jobs created. All studies agree that the number of jobs generated by these initiatives, even when combined, is insufficient and falls well short of the structural needs of the economy, to the extent that some policies have produced results that are almost negligible in relation to the expectations placed on them. This is largely due to the insufficiency of the resources allocated, but also to the lack of mechanisms for pooling resources between programs. However, efforts have been made, particularly in improving the employability of young people. In this regard, the CEE stands out as a benchmark unanimously praised in the literature for its effectiveness in strengthening skills and creating pathways to professional integration. It also stands out for its longevity in a context where policy discontinuity is the norm. However, the existence of selection bias in the choice of beneficiaries is a major obstacle highlighted in the literature, which calls into question the real scope of the scheme. Finally, another advance concerns the development of support instruments for project leaders. The rise of financial and technical mechanisms designed to support entrepreneurship is an undeniable achievement, even if these mechanisms suffer from the same limitations as those mentioned above, in particular their small scale, which considerably reduces their impact on the overall economic ecosystem. It should also be remembered that while entrepreneurship and self-employment offer interesting prospects, it would be illusory and counterproductive to make them the be-all and end-all of employment policies. The promotion of private initiative cannot replace a broader economic development strategy, driven by an industrialization policy capable of orchestrating intensive job-creating growth.

As for the shortcomings of youth employment policies in Senegal, they reveal systemic failures that call into question both the design of the measures and their implementation, and lead us to dismiss the hypothesis of marginal adjustment errors, revealing instead, the fragility of public action in terms of strategic coherence and institutional capacity to ensure its effectiveness. First, the lack of transparency in management accounts and the limited accessibility of accounting reports undermine the credibility of the programs. They also promote a lack of transparency, especially when we consider that the vast majority of young people are unfamiliar with these schemes. This reflects a serious shortcoming in terms of communication and information. The misappropriation of objectives observed in certain initiatives raises questions about the degree of autonomy of public action with regard to political instrumentalization, which discredits the redistributive function of employment policies. Furthermore, the lack of monitoring and evaluation is a real sticking point. The absence of ex-post evaluations, which is a consequence of the lack of reliable indicators on the quality and sustainability of the jobs created, condemns public action to a form of managerial drift, disconnected from its own stated objectives. Furthermore, the precarious nature of the opportunities offered shows a tendency for policies to perpetuate the very precariousness they claim to combat.

Institutional fragmentation, evident in the proliferation of stakeholders, the entanglement of objectives, the lack of coordination between structures, and the lack of clarity in public action, contributes to a dilution of efforts. The failure to capitalize on previous experiences limits the cumulative effectiveness of initiatives. Policies also suffer from a crisis of legitimacy, largely fueled by perceptions of inefficiency and suspicions of instrumental and clientelistic use. Measures often deemed disconnected from the realities on the ground reflect a mismatch between the needs of young people and the solutions provided. This situation is exacerbated by narrow programs linked to electoral cycles that prioritize short-term results. Strengthening participatory engagement therefore appears to be an essential condition for restoring the credibility of interventions and improving their social relevance. Finally, the lack of reliable statistical data and resources deprives decision-makers of the tools they need to effectively plan and adjust strategies to the realities on the ground.

However, employment policies have created job opportunities over the years, demonstrating that there is potential for action that should be consolidated. The government has gradually stepped up its efforts to develop initiatives that take into account the diversity of profiles. This willingness to adapt marks an important step toward integrating a differentiated approach to youth. However, public action faces the challenge of reconciling the specificity of individual trajectories with a coherent overall vision. While it is imperative to respond to the specific needs of different segments of youth, this should not lead to fragmentation or even atomization of strategies. A better alternative lies in striking a careful balance between recognizing individual differences and pursuing overall objectives.

There is also the question of striking a balance between structural and short-term solutions. Structural solutions, whether they involve reforming the education system, developing infrastructure, or diversifying the economy, require a long-term perspective. However, with young people increasingly eager to enter the labor market, these long-term measures may seem out of step with the urgent issues of the day. In this context, short-term solutions, such as rapid job creation programs or tax incentives for businesses, offer an immediate response, even if they are often limited in their sustainability. The government must therefore navigate between these two imperatives, in short, build an operational dialectic between the urgency of the response and the need for reform. It is incumbent upon the government to ensure that short-term management, which is certainly necessary to meet urgent expectations, is not carried out at the expense of strategic planning or institutional sustainability. This implies strategic resource management and, above all, careful prioritization of initiatives.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the success of employment policies also depends on their ability to be part of a cross-sectoral dynamic. Youth employment cannot be addressed in isolation from other national issues, such as education, health, and rural development. Mobilizing all available levers is essential to effectively address the complexity of the problem.

Conclusion

The issue of youth employment is back on the public policy agenda in Senegal, partly due to the centrality of this demographic group in terms of its statistical weight and its role in structuring social balances, and partly due to the emergence of young political figures, which is helping to bring the issue of integration back to the forefront of the political scene. While previous policies have failed to curb unemployment, any ambitious reconfiguration of public action in this area must necessarily build on the achievements and mistakes of the past, if only to avoid repeating the same dead ends. It is precisely in this perspective that the present review was conducted, with the central objective of analyzing, over a period covering the last two decades, the dynamics of success and the recurring obstacles that have marked the implementation of youth employment policies in Senegal. This undertaking has highlighted a proactive approach on the part of the state, reflected in attempts at readjustment made over the course of successive administrations, which have nevertheless yielded results, particularly in terms of job creation, improving employability, and promoting self-employment. However, these successes remain modest given the scale of expectations and the systemic nature of labor market vulnerabilities. Analysis of the selected studies reveals that policies suffer from major limitations, including weak strategic coherence, a lack of transparency, poor monitoring and evaluation, and the precarious nature of the opportunities created. Addressing these shortcomings requires upstream reform of public employment governance, which involves institutionalizing planning that breaks with the reactive approaches dictated by urgency or the political climate, and developing a culture of evaluation, which is essential for building learning-based public action. Such a renewal also requires a more nuanced understanding of young people themselves, ceasing to view them as a monolithic bloc and instead recognizing the diversity of their trajectories, aspirations, and vulnerabilities. Furthermore, it is important to restore the clarity of public action. The state must clarify the economic logic underlying its interventions: does it intend to act as a direct employer, or rather as a catalyst for an endogenous private sector capable of absorbing labor on a sustainable basis? The ambiguity of current policy directions, oscillating between a generalized call for entrepreneurship and a focus on vocational training that is not backed by a viable productive fabric, illustrates this lack of direction. Analysis of the results of this scoping review thus shows the need to jointly rethink governance, policy architecture, and resource management in order to move away from a model of intervention that is weak in terms of transformation.

Notes

[1] This research is part of Mr. Dieng's doctoral research and the establishment of a cross-disciplinary research focus on employment policies within the LASPAD at Gaston Berger University.

[2] According to the ILO, an unemployed person is anyone who is without work, available for work, and has sought work. The ANSD broadens this definition in Senegal, where the labor market is poorly structured, to include individuals who, although available, are not actively seeking work for reasons considered beyond their control.

[3] ANPEJ is an agency that was set up under President Macky Sall to promote youth employment in Senegal

Bibliography

African Union Commission & Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. (2020). Promoting youth entrepreneurship in Africa : A policy brief. https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/39541-doc-promoting_youth_entrepreneurship_in_africa_-_en.pdf

Akindes, F. (2022). Demography, Inclusive Growth and Youth Employment in Africa. Institute for New Economic Thinking. https://www.ineteconomics.org/uploads/papers/Africa-paper-3.pdf

ANSD (Agence nationale de la statistique et de la démographie). (2015). Situation économique et sociale du Sénégal en 2012. https://www.ansd.sn/sites/default/files/2022-12/4-emploi-SESN2012.pdf

ANSD (Agence nationale de la statistique et de la démographie). (2024). Enquête nationale sur l’emploi au Sénégal : premier trimestre 2024, note d’information. https://www.ansd.sn/sites/default/files/2024-07/Rapport_enes_T1_2024_VF.pdf

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies : Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19‑32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Ba, A., Bjornson, L., Fall, N. S., Gillis, K., Gorry, G., Koné, O., Robin, L., & Sow, A. (2012). L’employabilité des jeunes du Sénégal : séminaire International 2012. Une initiative du CECI et de l’EUMC. https://seminaireinternational2012.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/rapport-final-ej.pdf

Banque mondiale. (2007). Senegal Looking for Work—The road to prosperity (volume I : rapport 40344 ; numéro 40344). World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/51692681-8666-568f-bb28-5e3b3cd55163/content

Banque Mondiale. (2023). Emplois vulnérables, total (% des emplois)— Sénégal. World Bank Open Data. https://data.worldbank.org

Barlet, S., Baron, C., & Lejosne, N. (2011). Métiers porteurs : le rôle de l’entrepreneuriat, de la formation et de l’insertion professionnelle. Document de travail. Agence française de développement (AFD). https://gret.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/111-document-travail.pdf

Barry, I., & Kane, A. (2022). Durée de transition école premier emploi au Sénégal. 12, 4‑25.

Baumann, E. (2016a). Chapitre V : Les politiques publiques : inciter au travail. In Sénégal, le travail dans tous ses états (pp. 201‑226). Presses universitaires de Rennes. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.46805

Baumann, E. (2016b). Chapitre VI : Au fil du temps : des projets « au service » de l’emploi. In Sénégal, le travail dans tous ses états (pp. 227‑248). Presses universitaires de Rennes. https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.46806

Becker, G. S. (1975). Human capital : A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (2nd edition). National Bureau of Economic Research : distributed by Columbia University Press.

Bourkane Ly, L., Cabral, F. J., Mamno Wafo, V. L., & Diagne, K. (2019). L’impact du Plan Sénégal émergent (PSE) sur l’emploi. Groupe de la Banque africaine de développement. https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/documents/projects-and-operations/rapport_emploi_senegal_10-12-2019.pdf

Busson, S. (2021). Skills Development & Youth Employability In West Africa. Observations on the state of TVET and good practices from Senegal, Ghana, Ivory Coast and Nigeria. https://www.adeanet.org/sites/default/files/resources/report_africavf_compressed.pdf

Cabral, F. J., Diakhaté, I., Gavlo, K., Fall, M., & Ndao, S. (2014). Diagnostic sur l’emploi des jeunes au Sénégal. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---africa/---ro-abidjan/---sro-dakar/documents/publication/wcms_339500.pdf

Card, D., Kluve, J., & Weber, A. (2018). What Works? A Meta Analysis of Recent Active Labor Market Program Evaluations. Journal of the European Economic Association, 16(3), 894‑931. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx028

Challenge Fund for Youth Employment. (2021). Scoping Report—Senegal. Challenge Fund for Youth Employment (CFYE). https://fundforyouthemployment.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Scoping-Report-Senegal-2021-Challenge-Fund-for-Youth-Employment.pdf

Conseil économique social et environnemental. (2013). Rapport général des travaux de l’année 2013. CESE. https://cesesenegal.sn/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/RAPPORT-GENERAL-2013_CESE.pdf

Conseil économique social et environnemental. (2021). Rapport des travaux de la première session ordinaire du 23 février au 09 avril 2021. CESE. https://cesesenegal.sn/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/rapport-session-2021-copie.pdf

Délégation Générale à l’Entrepreneuriat Rapide des Femmes et des Jeunes. (2024). La DER/FJ au service de l’entrepreneuriat (2018-2023). https://www.der.sn/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/LA-DERFJ-AU-SERVICE-DE-LENTREPRENEURIAT-2018-2023.pdf

Diagne, K. B. (2024). Migration et emploi des jeunes : Quelles alternatives ? [Policy Brief]. https://www.ipar.sn/IMG/pdf/police_brief_-_policy_brief_migration_et_emploi_des_jeunes_def_indd.pdf

Diallo, M. A. (2023). Au centre des priorités des jeunes sénégalais : La gestion de l’économie, l’insécurité et l’emploi. Afrobarometer, 711. https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/AD711-Priorites-des-jeunes-senegalais-Economie-insecurite-et-emploi-Afrobarometer-4oct23.pdf

Diallo, M. A., & Diallo, H. (2021). Malgré une baisse du chômage, les Sénégalais réclament plus d’efforts du gouvernement en matière de création d’emplois. Afrobarometer, 499. https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ad499-senegalais_reclament_plus_defforts_du_gouvernement_en_matiere_de_creation_demplois-depeche_afrobarometer-17dec21.pdf

Diallo, M., Ndiaye, S., Diop, A. A., & Dior Diop, M. (2022). Nouvelles modalités et nouveaux thèmes pour les avis scientifiques en Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre : focus sur l’employabilité des jeunes et l’entrepreneuriat féminin. Cas du Sénégal. Conseil pour le dévelopement de l’Afrique (CODE-Africa). https://www.code-africa.net/app/uploads/Rapport_Pays_Se%CC%81ne%CC%81gal_vf_ok.pdf

Diallo, T. M., Dieye, A., Ronconi, L., & Sinzogan, C. (2023). What works for Youth Employment in Africa : A review of youth employment policies and their impact in Senegal. Working Paper 2023-17. https://mastercardfdn.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Youth-Employment-Senegal-Working-Paper.pdf

Doeringer, P. B., & Piore, M. J. (1971). Internal Labor Markets and Manpower Analysis : With a New Introduction. Routledge.

Échevin, D., Sylla, M. B., Ly, M. A., & Seck, F. G. C. (2013). Youth employment in northern Senegal : Creating job opportunities for young people. GLOBAL PARTNERSHIP FOR YOUTH EMPLOYMENT. https://iyfglobal.org/sites/default/files/GPYE_Assessment_Creating_Opportunities_for_Youth_6.pdf

Fox, L., & Thomas, A. (2016). Africa’s Got Work To Do : A Diagnostic of Youth Employment Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Economies, 25(suppl_1), i16‑i36. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejv026

Kamga, F. (2019). Améliorer les politiques d’emploi des jeunes en Afrique francophone. Centre de recherches pour le développement international (CRDI). https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b5ed8f47-3ddd-44bc-ade4-e412858bccb1/content

Kane, A., Ablouka, G., & Dogbe, A. K. (2020). Les déterminants de l’arbitrage entre entrepreneuriat et salariat au Sénégal. https://ofe.umontreal.ca/fileadmin/ofe/documents/Actes/Conf_OFE_CIRPEC_2020/Texte44_Kane.pdf

Kane, A., Barry, I., Marone, M., Ndoye, M. L., Thiongane, M., & Seck, A. (2018). Projet : Améliorer les politiques d’emploi des jeunes en Afrique francophone/RAPPORT ENQUÊTE SÉNÉGAL. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/6a2269ad-456b-47a6-96cb-c4262e0961bd/content

Kane, A., Ndoye, M., & Dogbe, A. K. (2022). Programmes de stage et accès à l’emploi : une application à la Convention nationale état-employeurs du secteur privé au Sénégal. Revue d’économie du développement, 28(4), 47‑81. https://doi.org/10.3917/edd.344.0047

Kane, A., Ndoye, M. L., & Seck, A. (2021). Efficacité du dispositif d’accompagnement à l’insertion professionnelle des jeunes au Sénégal. African Development Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12486

Kluve, J., Puerto, S., Robalino, D., Romero, J. M., Rother, F., Stöterau, J., Weidenkaff, F., & Witte, M. (2019). Do youth employment programs improve labor market outcomes? A quantitative review. World Development, 114, 237‑253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.10.004

Kraft, K. (1998). An evaluation of active and passive labour market policy. Applied Economics, 30(6), 783‑793.

Labrune-Badiane, C. (2016). Parcours et portraits de la jeunesse au chômage en Casamance : expériences vécues et perspectives d’avenir. Proceedings of the African Futures Conference, 1(1), 49‑60. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2573-508X.2016.tb00022.x

Massing, F. P. N., Kane, N. O. D., Sy, T., & Liboudou, L. (2014). Les déterminants de l’entrepreneuriat des jeunes en Afrique de l’Ouest : le cas de la Mauritanie et du Sénégal. Fonds de recherche sur le climat d’investissement et l’environnement des affaires (CIEA), 81/14. https://pefop.iiep.unesco.org/en/system/files/resources/Pef000172_Kane_Sy_NtepMassing_Liboudou_Entreprenariat_Jeunes_AfriqueOuest_2014_0.pdf

McKenzie, D. (2017). How Effective Are Active Labor Market Policies in Developing Countries? A Critical Review of Recent Evidence. The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2), 127‑154. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkx001

Ministère de la Jeunesse, de l’Emploi et de la Promotion des valeurs civiques. (2014). L’emploi des jeunes au Sénégal : une priorité nationale. (Forum national sur l’emploi des jeunes). https://pefop.iiep.unesco.org/fr/system/files/resources/Pef000103_MJEPVC_Rapport_Forum_National_Emploi_Jeunes_SN_2014.pdf

Ministère de l’Économie, des Finances et du Plan. (2018). Rapport annuel d’activités—Édition 2018. https://acces-universel-electricite.gouv.sn/IMG/pdf/rapport-annud4ed-2.pdf

Ministère de l’Économie, du Plan et de la Coopération. (2021). Programme d’urgence pour l’emploi et l’insertion socioéconomique des jeunes—Xeyu Ndaw Ni. https://economie.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/2021-07/Brochure%20Xeyu%20Ndaw%20Gni-version-finale_compressed.pdf

Ndao, P. I. (2010). Projet de politique nationale de l’emploi. République du Sénégal - Bureau international du travail. https://webapps.ilo.org/static/english/emplab/download/nep/senegal/senegal_national_employment_policy_2010.pdf

Ndoye, M. L. (2020). Efficacité du dispositif d’appui à l’insertion des jeunes sur le marché du travail au Sénégal [université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (Ucad)]. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/2d28477a-8a72-4c1f-9b48-50333b116ccc/content

Obadić, A. (2006). Theoretical and empirical framework of measuring mismatch on a labour market. Proceedings of Rijeka Faculty of Economics: Journal of Economics and Business (zbornik@efri.hr); 24(1), 24.

Organisation internationale des employeurs. (2024). Politiques de la jeunesse et de l’emploi en Afrique : Défis, aspirations et opportunités. Organisation internationale des employeurs (OIE), Commission africaine de la jeunesse. https://www.ioe-emp.org/index.php?eID=dumpFile&t=f&f=159961&token=a9a76345735a0b81791f23521879fd15e49ce86f

Ozor, N., & Nyambane, A. (2024). What is the place of science, technology, and innovation in youth employment in Senegal? 68. https://atpsnet.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Technopolicy-Brief-No.-68-What-is-the-Place-of-Science-Technology-and-Innovation-in-Youth-Employment-in-Senegal.pdf

PSE (Plan Sénégal émergent). (2023). Plan Sénégal émergent. Plan d’actions prioritaires 3 : 2024-2028. https://www.finances.gouv.sn/app/uploads/PSE-PAP-3-2024-2028.pdf

Sambou, O. D. (2020). Insatisfaits de leur gouvernement, les jeunes sénégalais évoquent la recherche d’emploi comme principale raison d’émigrer. Afrobarometer, 405. https://www.afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ad405-migration_des_jeunes_senegalais-depeche_afrobarometer-bh-13nov20.pdf

Sané, S., Dione, D., & Sané, M. (2022). Service public de l’emploi pour une politique efficace en matière d’insertion professionnelle au Sénégal : une analyse des programmes de promotion d’emploi des jeunes. Revue de gestion et d’économie, 10(1 & 2), art. 1 & 2. https://doi.org/10.34874/PRSM.jbe.36904

Sané, S., Dione, D., & Sané, M. (2023). Politiques publiques et création d’emplois au Sénégal : une analyse en termes d’efficacité de programmes de promotion d’emplois des jeunes. (37). 1(37). https://revues.imist.ma/index.php/REGS/article/view/38066

Sarr, M. D. (2004). Poverty Reduction Strategy and Youth Employment In Senegal. https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/social/papers/urban_sarr_prsp.pdf

Seck, A. (2004). Insertion professionnelle des jeunes diplômés au Sénégal : analyse de la situation. Contraintes et perspectives. Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar. Monographie de fin d’étude pour l’obtention du certificat d’aptitude aux fonctions d’inspecteur de l’éducation populaire de la jeunesse et des sports. https://beep.ird.fr/collect/inseps/index/assoc/MO04-09.dir/MO04-09.pdf

Sylla, N. S. (2023). Pour un plein-emploi décent en Afrique : réflexions sur la garantie d’emploi. Fondation Rosa Luxemburg (Bureau Afrique de l’Ouest). https://rosalux.sn/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/DOCUMENT_TRAVAIL_2023_RLS-002.pdf

Timbuktu Institute. (2020). Échec des dispositifs pour l’emploi : une jeunesse sénégalaise « anxieuse », « abandonnée » et « sans horizon » (étude Timbuktu Institute). https://timbuktu-institute.org/index.php/toutes-l-actualites/item/376-echec-des-dispositifs-pour-l-emploi-une-jeunesse-senegalaise-anxieuse-abandonnee-et-sans-horizon-etude-timbuktu-institute

Tine, B., & Sall, A. (2015). Les trajectoires d’emplois des jeunes au Sénégal : entre emplois « faute de mieux » et projet professionnel. Série de documents de recherche (version provisoire). https://www.cres-sn.org/les-trajectoires-demplois-des-jeunes-au-senegal-entre-emplois-faute-de-mieux-et-projet-professionnel/

Tsambou, A. D., Diallo, T. M., & Benjamin, F. K. (2022). Programmes d’appui à l’emploi et employabilité des jeunes dans les secteurs pourvoyeurs d’emplois au Sénégal (note de politique générale). Consortium pour la recherche économique en Afrique. https://publication.aercafricalibrary.org/items/5bd610c5-f093-427e-b4eb-6a344623dbba

Tsambou, A. D., Diallo, T. M., Kamga, B. F., & Asongu, S. A. (2024). Impact of employment support programs on the quality of youth employment: Evidence from Senegal’s internship program. Sustainable Development, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.291

To cite this paper:

APA

Dieng, M., Diallo, M. A., & Ba, M.-P. (2025). Unemployment and Youth Employment in Senegal: A Review of the Scope of Achievements, Shortcomings, and Structural Limitations of Public Policies. Global Africa, (11), pp. 178–192. https://doi.org/10.57832/833y-ek07

MLA

Dieng, Mouhammad, Mamadou Aliou Diallo, and Mame-Penda Ba. "Unemployment and Youth Employment in Senegal: A Review of the Scope of Achievements, Shortcomings, and Structural Limitations of Public Policies." Global Africa, no. 11, 2025, pp. 178-192. doi.org/10.57832/833y-ek07

DOI

https://doi.org/10.57832/833y-ek07

© 2025 by author(s). This work is openly licensed via CC BY-NC 4.0